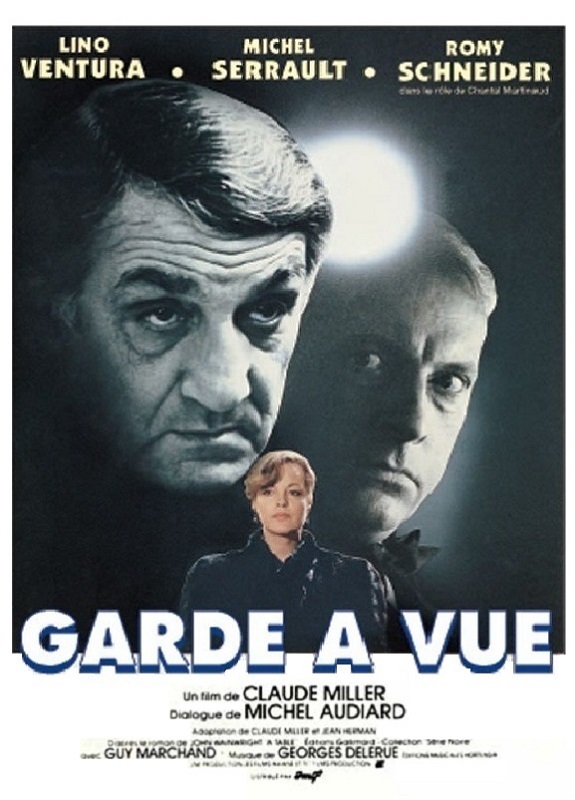

‘Garde a vue‘, made in 1981, brings together on screen two of the super-stars of French cinema from the ’60s and’ 70s, each of them in one of their last films, although neither their age nor their artistic form indicates anything about the close endings. Romy Schneider was in her penultimate film, she would die a year later, at only 43, with a heart weakened by illness and by the various excesses of her short but intense life. Lino Ventura was 62 years old when ‘Garde a vue‘ was filmed, he would make six more films (including a formidable Jean Valjean in ‘Les Misérables‘) but he would also leave this world relatively quickly, in 1987. The film’s director, Claude Miller was not very young, but this was only his third movie. But what a movie! ‘Garde a vue‘ describes a few hours of interrogation in a police station, but the seemingly trivial investigation and confrontation between the police and the suspect develops into a subtle game of forces and a gradual revelation of layers of reality that do not necessarily lead to the knowledge of the truth.

The formula is classic. Inspector Antoine Gallien (Lino Ventura), apparently a conscientious bureaucrat of the police, proves to be intelligent and able to use any means to obtain the confession of the main suspect in the rape and the murder of two eight-year-old girls. Lawyer Martinaud (Michel Serrault), rich and arrogant, seems to the audience the perfect suspect, not only because of social class differences but especially because he gets into trouble with a tangle of lies that seem to aim not so much to prove that he is innocent, but rather to defend a moral reputation that erodes as the investigation progresses. And if summoning the suspect on New Year’s Eve is not enough, the police will use two more means of pressure – the judicial procedure called ‘garde a vue’ which allows the suspect to be detained for questioning without the presence of a lawyer, and the testimony of Martinaud’s wife (Romy Schneider) whose relationship with her husband has been marked by trauma since the beginning of the marriage.

The screenplay (which adapts a novel ‘serie noire’ by American writer John Wainwright and moves it into the French police and judicial reality) manages in an extremely subtle way to make us advance in the knowledge of the psychology of the characters and highlights the relativity of the notions of truth and justice. The crimes that Martinaud is suspected of are horrible and would justify almost any method of finding out the truth. But is what we see and what we hear the truth? Not even at the end of the movie can we be 100% sure of that. Moral judgments are not equivalent to judicial reality. What we see on the screen is a version, but we will never know for sure what happened. Confession does not necessarily mean guilt either. Ventura and Schneider’s acting performances are remarkable, but the most intense creation belongs to Michel Serrault, who embodies a character who tragically breaks apart in front of our eyes. The dialogues and situations have consistency and credibility, and this drama, which takes place mostly in a police investigation room, manages to involve us far beyond the experience of a routine crime drama.